What is Intelligence? Intelligence can mean many different things depending on the context. If we perform a quick online search, the following definition will be one of the first results:

Let us focus on the second definition: “The collection of information of military or political value.” Many intelligence experts will agree that this statement is mistaken. Considering intelligence to be synonymous with information is a more common issue than one might imagine, and quite often, the error extends all the way back to intelligence collection. One can readily collect information; however, information can only be classified as intelligence after undergoing analysis.

There is consensus amongst Law Enforcement and Intelligence Agencies that intelligence is not what is collected, but rather the data that is produced after the collected information has been evaluated and analyzed: Information plus analysis equals intelligence. It is utterly important to think of intelligence as a product—something that has been processed—rather than the raw material of information.

A few years ago, I heard a catchphrase that has stayed with me and defines my understanding of what intelligence is. “Intelligence is information that has been raised to a high degree of certainty.” The discoveries we make serve as a basis for uncovering further information, which must then be shared since intelligence is only meaningful when communicated. However, it is essential for analysts to establish the validity of their findings in the eyes of the end-users and decision-makers. Building confidence in intelligence is a gradual process that requires time and effort.

By applying intelligence analysis techniques to the information you gather, you can increase the level of certainty in your predictions, turning them into actionable intelligence items. With that in mind, this piece will focus on sharing effective techniques for analyzing information and disseminating it in the most impactful way.

The Ultimate Purpose of Intelligence 🔗︎

Sir Francis Bacon’s quote “Knowledge is power” suggests that having knowledge empowers individuals to make informed decisions. In today’s fast-paced world, knowledge has become more critical than ever before. Whether it is in the field of technology, politics, or medicine, having knowledge can give an individual an advantage over others.

The ultimate purpose of intelligence is to provide relevant elements that allow an informed decision to be made. Two of the major objectives of intelligence are the imperative need to minimize the impact of surprise and reduce uncertainty in decision-making.

Analysis and decision-making share risks, but each also requires its own precautions. Take risk assessments for example. Risk assessments entail making decisions based on resources, and never losing sight of the fact that resources, in terms of security, are limited.

As mentioned earlier, intelligence is analyzed information. The intelligence we are generating builds upon strategic information from tactical-strategic knowledge gathered through:

- Past lessons learned

- Present for containment

- Future anticipation

Three Types of Intelligence 🔗︎

Depending on its scope and intended use, intelligence can be divided into the following categories:

Strategic Intelligence 🔗︎

Helps to define objectives and establish general policies to achieve the goals set by the State (national objectives). Consolidates basic intelligence.

Tactical Intelligence 🔗︎

Assists in the planning and design of the necessary actions to achieve the objectives of an operation. Methodology of the search plan.

Operational Intelligence 🔗︎

Assists in the execution of concrete actions to accomplish a mission.

Producing and Presenting Intelligence 🔗︎

We now know what intelligence is and how we can categorize it according to its purpose. But how do we go about producing it, and in the best way possible?

Colin Powell had a rule for intelligence officers. As an intelligence officer, it is your responsibility to:

- Say what you know (facts)

- Say what you don’t know (information gaps)

- And only then, you are allowed to say what you think (analysis)

These three so-called “steps” are a great guide on how we can organize and present an intelligence report or a situation briefing.

First, when we are structuring and analyzing the information we’ve collected, our first goal should be to develop a deep comprehension of the topic itself. When it comes to writing an intelligence report or brief, the title is a crucial element that can either attract or deter readers from reading the document. The title should be a concise and accurate reflection of the content of the document. However, coming up with the perfect title is not always an easy task, and it is something that is often worked out over time.

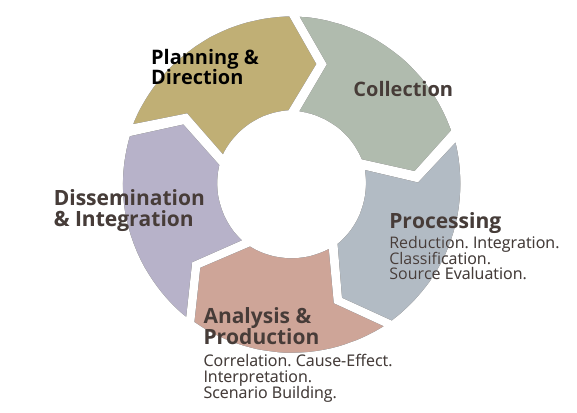

Next, if we go back to the Intelligence Cycle, these are the expected results from processing and analysis of the information we’ve gathered:

If we translate these goals into action verbs, we have a clearer picture of the path the intelligence analyst must follow to produce intelligence. Intelligence analysis is the process of collecting, evaluating, and interpreting information to create actionable intelligence. While it is a crucial component of national security and law enforcement, it can be a complex and challenging process. Some of the particular challenges of intelligence analysis include:

- Lack of Data: Sometimes, there may not be enough data available to support an accurate analysis. This can be due to a lack of sources, unreliable sources, or limited access to sensitive information.

- Complexity of Data: The data collected may be complex, technical, or difficult to understand. This can make it challenging to extract meaningful insights and create actionable intelligence.

- Biases: Intelligence analysts may have biases based on their personal beliefs, experiences, or political affiliations. These biases can influence the interpretation of data and lead to flawed analysis.

- Misinformation: The proliferation of false or misleading information can make it difficult to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate data. This can result in flawed analysis and poor decision-making.

- Time Constraints: Intelligence analysis often operates under tight timelines, with a need to provide timely and accurate intelligence to decision-makers. This can lead to rushed analysis, incomplete data, and potential errors.

- Security Concerns: Intelligence analysts often deal with sensitive or classified information, and the security concerns associated with handling this data can be challenging. This includes maintaining confidentiality, preventing leaks, and ensuring the security of data storage and transmission.

To minimize the loss of objectivity in our research and to facilitate working with our colleagues, we can use structured techniques for intelligence analysis.

Richards Heuer and Randolph Pherson are two leading scholars of structured analytic techniques. Both were strong advocates of group work, and the techniques they present move away from individual efforts and encourage teamwork.

Today, we will talk about two of these techniques and how their implementation can enhance our analysis. It is very likely that you already utilize them to some degree, however, it never hurts to review how we can structure and organize our thought process to develop an objective intelligence report, and one which reaches that level of certainty, which can fulfill the needs of the end user.

Structured Brainstorming 🔗︎

There’s nothing like a brainstorming session. Regardless of the structure of the organization, we can greatly improve these sessions by:

- Avoiding higher hierarchy staff presence, so as to promote an open, judgement-free atmosphere and;

- Inviting an external element that has little or no knowledge of the topic under discussion, to avoid groupthink and stimulate divergent thinking

However, brainstorming can get out of hand sometimes. It is advisable to appoint a moderator, and to define time limits for proposing ideas, discussion, and conclusions.

Multiple Hypothesis Generation 🔗︎

A hypothesis is a possible explanation that will be put to the test by gathering and examining the available data. It is a declarative argument that has not been shown to be true. Rather, it is an “informed guess” based on observations that can either be confirmed or disproved through further investigation or analysis.

According to Heuer, a good hypothesis should satisfy the following criteria represented by the mnemonic STOP:

- Statement, not a question

- Testable and falsifiable

- Observation—and knowledge-based

- Predicts anticipated results clearly

This technique helps the analysts and the investigators to think broadly and creatively. By developing a list of hypotheses that can be scrutinized and tested over time against existing information (what we already know to be true), we can avoid being surprised by our main assumption or conclusion that turns out to be wrong. It is especially useful when a high level of uncertainty exists around the outcome, or when there are many variables involved in the analysis.

The experts recommend brainstorming first, and then following the steps below:

- Ask each group member to list up to three more explanations or theories on an index card.

- Gather the cards, and then present the findings on a whiteboard. To avoid any duplicates, combine the list.

- Use additional individual and group brainstorming strategies, such as cluster brainstorming, to uncover important forces and factors.

- Categorize the hypotheses into clusters based on their similarities and assign a name to each group.

- To generate new thoughts, rephrase the issue and consider a contrarian approach.

- Update the list of alternative hypotheses. Try to maintain the concept of Mutual Exclusivity if these hypotheses will be used in Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH), meaning that if one hypothesis is correct, all opposing hypotheses must be incorrect.

- Ask the group to elaborate on each claim by posing the standard set of journalistic questions: Who, what, where, when, and how.

- Select the most promising hypotheses to investigate further.

These are just two of the many techniques to improve our intelligence analysis and increase the degree of certainty of the hypothesis that we are going to present to the end user.

In the realm of intelligence, a single accurate judgment, prediction, or recommendation can potentially shape the course of history. However, the full impact of an intelligence report is often unknown, underscoring the critical importance of precision and reliability in the field. Sometimes it may affect only one department, sometimes a nation.

From Information to Actionable Intelligence 🔗︎

If you want to gain even more insight into how intelligence is created and discover how analysts utilize intelligence collection disciplines to ensure high-quality intelligence, we encourage you to watch our deep dive on breaking down intelligence. Simply fill out the form below to watch it now.

Download the resource

If you found this article useful and would like to receive more updates on intelligence gathering or other related topics, you can follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Mastodon, or sign up to our email newsletter,

Until the next one and happy investigating!

About the Author 🔗︎

Daphnée Aguilar 🔗︎

Daphnée is a Criminologist with more than 10 years of experience as an Intelligence Officer. She specialized in developing actionable intelligence for identifying, preventing, and neutralizing threats and risks from Transnational Organized Crime. Driven by the feminist movement, her last research was on the Effects of Gender and Racial Bias on Gender-Based Violence Policies. She considers herself a professional taco taster.